Shrovetide - Spirit of the Game

Article in Derbyshire Life March 2020

Words: Penny Baddeley

Photos: Nigel Gibson

Wheathills has recently completed an intricate sculpture – commissioned by Dr Dallas Burston who turned up the ball for the Royal Shrovetide Match in 2017 – which captures the essence of the game.

Since at least 1667, each Shrove Tuesday and Ash Wednesday the exhilarating and at times ear-splitting spectacle of the Royal Shrovetide Football Match has taken place in Ashbourne. The boisterous and thrilling sporting event played over two eight-hour periods still has all the colour, excitement and drama of a Shakespearian play. It begins at 2pm when a unique ball, created by Terry Brown and painted by Simon Hellaby, is turned up for the waiting crowds from a plinth in the town centre by a celebrated, sometimes royal, but often local dignitary.

Nigel Heldreich, the owner of Wheathills – creators, conservers and restorers of fine furniture and decorative art – has lived and worked in and around Ashbourne all his life. He first attended a match at the age of eight with his father Harold and from the time he started out in business in 1985, has been a regular visitor-player, attending with friends and family and soaking up the ‘phenomenal camaraderie’ as well as the mud and water. Over the years he has both touched and run with the ball – and been knocked out several times in the process – so he was delighted when Wheathills was commissioned in December 2016 to create a piece of artwork to commemorate and record the game for posterity.

The challenge was set by retired GP and pharmaceuticals entrepreneur Dr Dallas Burston who was born and raised in Ashbourne and invited to turn up the ball on 28th February 2017. Dr Burston explained: ‘To be invited to turn up the ball is the highest accolade anybody from Ashbourne could be accorded. It was the proudest moment of my life and I wanted a historical record of the day and the people involved.’ His artistic brief to Wheathills was short but exacting. He urged them to create ‘the most amazing thing you have ever made.’

Nigel added: ‘He also told me that he wanted me to capture the essence of the game as one second in time. What a challenge! I felt a rush of adrenalin, and fear – almost as if I was back as a boy at my first experience of the Game!’

Wheathills craftsmen are specialists in creating highly personalised bespoke furniture and beautiful memory boxes with a secret and personal narrative that is uniquely identifiable to the owner, which lends to them what Nigel considers is an almost spiritual dimension.

Nigel, 51, had not witnessed the cut and thrust of the historic game for many years and decided to place himself in the middle of the action of the 2017 game. Armed with a camera on a 25ft-high pole, he fought his way into the ‘hug’ to capture some close-up photographs. Despite being knocked over, suffering kicked shins, dislocating a finger and chipping the bone in his thumb he managed to get some ‘fantastic images’. ‘I could see a multitude of emotions in everyone’s face. The players are absolutely focused on getting their plan executed. They manoeuvre themselves, make tactical false runs and you can see the emotion in their faces as they communicate with each other.

Some visitors are drawn in by the enthusiasm and then there are others on the periphery frightened that the ball will come their way. I was registering these emotions – elation, screaming and laughing, genuine fear and aggression – and realised the focus wasn’t the ball, the game or Ashbourne, it was the waves of different emotion coming from this body of people. I thought to myself where else on earth could you see that? This was what was unique about the event.’

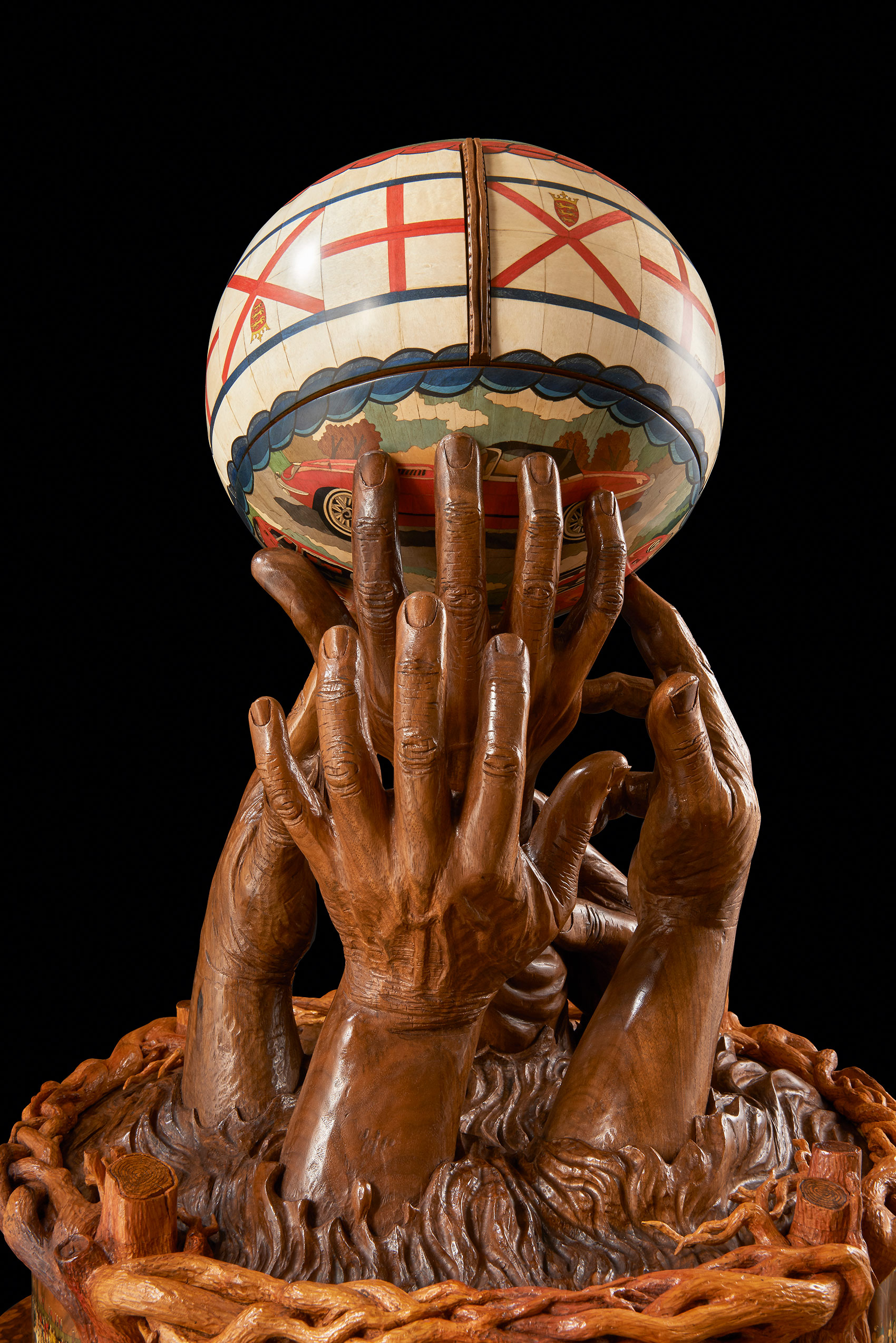

Another moment of inspiration came on the second afternoon of play when the ball was manoeuvred into the duck pond – a tactic which separates enthusiastic spectators from serious players. ‘You could see expectations rising for the group in the water who had a clear chance of getting the ball, the dedication on their faces was tremendous. Hands went up and they were pulling at one another’s clothing and wrists and pulling each other’s fingers off the slippery ball. The water was pushing their bodies away from each other, so all that remained was a battle of wrists. You could see hands and fists fighting through the splashing and the spray, and I knew that was the moment to capture. Their hands revealed each player’s emotions and that had to be the substance of the artwork. I could never have come up with the idea without being part of the event though. I would not have been able to create an honest piece of work.’

With the focal point decided, other parts of the story went into making the piece complex and modular. The dramatic sculpture would surmount an intricately designed and decorated memory box set on a magnificent stand.

Nigel also wanted the work to capture a sense of where and when the game was played – both its geographical location and the specific time of year. It also needed to record Dr Burston’s presence and reflect his personality. The sculpture was his fourth commission for Wheathills, so they had become well-acquainted over the years.

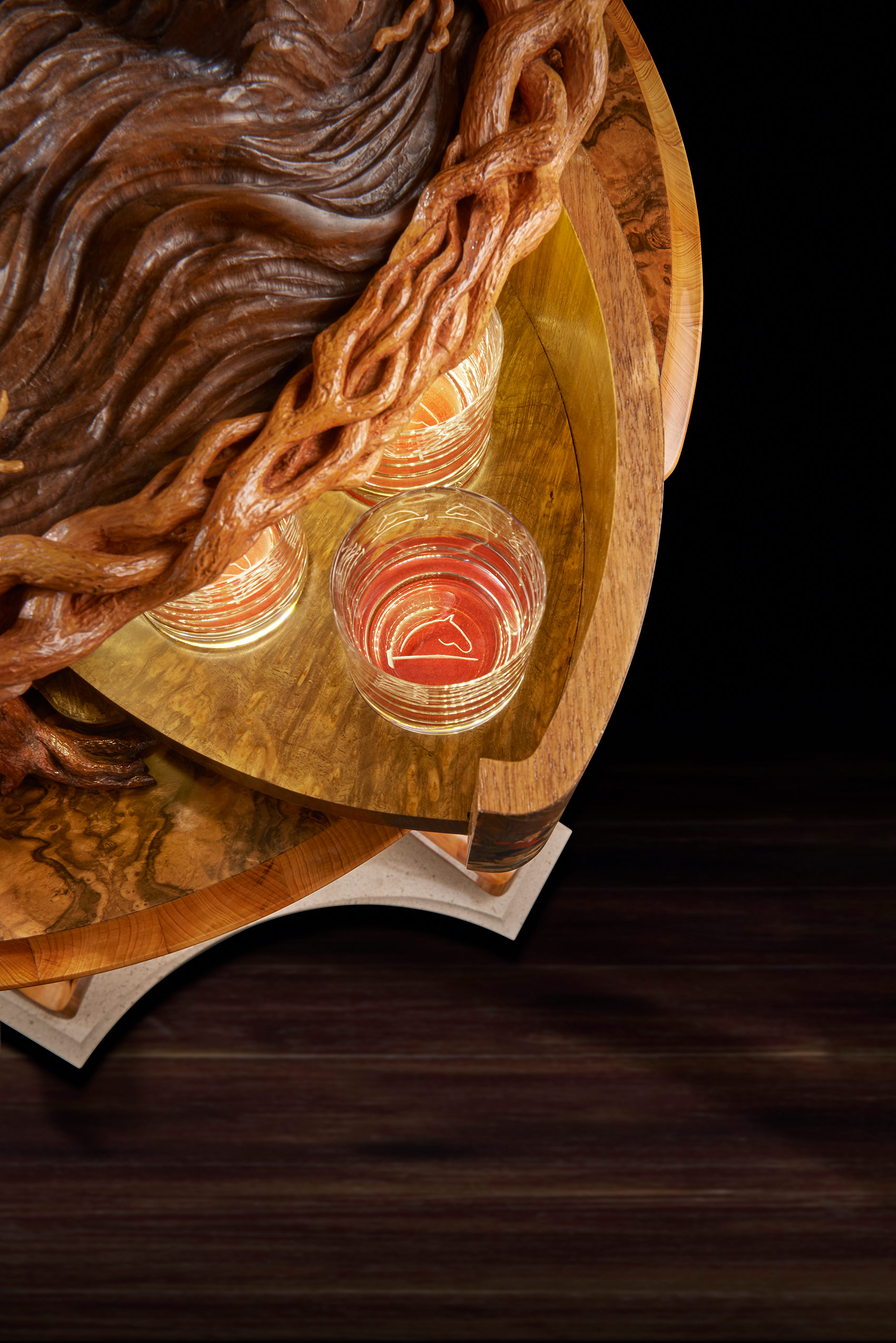

Nigel said: ‘Dr Burston is an exceptionally clever individual and inventor with a tremendous imagination and he’s also a playful person who enjoys fun. I wanted to bring into play the characteristics of the man in the sculpture so I thought our memory box sculpture should tantalise him with a hidden tantalus! I knew that he enjoyed the odd glass of whisky and sometimes the obvious is the right thing to do. I didn’t want to create a work of art that would just stand in a corner. I want it to be used. In this way the sculpture would be something he would interact with on good days with friends and using it would be a means of re- visiting his experience of turning up the ball, which is a huge honour for any Ashburnian.’

To characterise the piece the tantalus would be carefully hidden inside a detailed replica of the ball Dr Burston had turned up and the ball, larger than a traditional football, would be held aloft by the hands of the players.

Nigel made concept notes for his craftsmen, acknowledging, ‘I was steering the thing, but all the hard work is done by the craftsmen and women who absolutely poured their hearts into this project.’

One of the most technically challenging aspects was to make the ball. It took six weeks and involved, as Nigel said, ‘capturing perfectly not only its shape but also its handstitched details, bumps and dents.’ The original ball was cast in bronze resin and the cast used as a pattern over which vibrantly coloured marquetry images could be drawn, designed, spaced and created. Next a hollow walnut ball, identical to the bronze resin cast, was created from 120 segments of walnut, each walnut layer cut in decreasing size to create the perfect curve. This was then lathe-turned and carved with the dents and bumps of the original. The marquetry, designed on the resin cast, was transferred to the walnut ball. The whole was cut in three and the three parts micro-engineered with hand-made knuckle hinges, levers and pistons so that, at the push of a secret button concealed in the marquetry, it would open to reveal a hand- blown English crystal decanter set on an up-lit carved walnut cushion. The interior lid of the sphere is inlaid with a ‘yew tree of life’, delicately carved in yew wood to symbolise tradition, strength and success.

Four carved hands emerging from water hold the ball aloft, forming the top of a memory box. We can identify the elation and sense of anticipation of the player whose fingertips are about to gain the ball, locate the anger of the player who knows he’s out of the running and can only reach in frustration at the shirt sleeve of a competitor. In a flash the intense physicality of the game and the environment in which it is played have been captured. Nigel’s film footage, drawings, new photographs, plasticine maquettes and plaster casts were all stages in creating the hands. In fact, it’s the carver’s own hands that are represented in the finished walnut pieces – a masterly self-portrait of muscle, with cuts and even a broken fingernail. The memory box itself is decorated with four brightly coloured marquetry panels of scenes from the game which feature 75 tiny detailed portraits of people who were present. At a presentation for those who attended the match at Ashbourne British Legion, players who spotted themselves in Nigel’s photographs were asked to pose for another photograph which was used to create their marquetry portrait. As Nigel said: ‘In order that the entire sculpture sings, every element has to be right!’

The memory box is also carved with a walnut tree and at the release of a concealed button, the sides open to reveal engraved crystal glasses. A further drawer, to keep safe mementos of the match, can be released with the press of a second secret button. The sculpture sits on a specially created burr walnut and yew wood table – on which it can rotate. The stand’s four delicate serpentine legs have been cleverly engineered to rest on the short grain of the wood – furniture legs usually rely for strength on the long grain cut. ‘We wanted to create that sense of wonder, to make the viewer question how on earth it worked. I was really trying to put the impossible into a piece and to encourage curiosity and interaction with it,’ said Nigel. Reflecting the time of year of the Royal Shrovetide game, the hand- carved, hollowed-out legs are decorated with climbing ivy that aligns with the walnut trees on the memory box.

For Nigel, the sculpture needs to be taken as a whole. ‘It’s about all the elements of Ashbourne’s Shrovetide. Our sculpture defines the time of year, the story of the day, the passion of the players and the actual ball that was played. It has taken nearly two years to complete, involving myself, a cabinet maker, a French polisher, artists, a marquetry artist and a carver. It’s phenomenal. Words can’t describe what it feels like to get a commission like this, which is local and had few boundaries. It was a fantastic brief. And everyone here at Wheathills feels they have contributed, not just to recording and celebrating local history but to creating a piece of history themselves.’ Dr Burston is also delighted with the result: ‘The skill in this piece is in Nigel’s interpretation of what we wanted to achieve, taking all the elements into consideration and getting it right. You need to live and breathe Shrovetide to understand it. If I had not known Nigel this piece would not have happened because no one else understands it like him.

The piece is without doubt a vibrant representation of the Shrovetide game. I wanted the essence of the game captured and Nigel has faultlessly delivered it. He’s a genius!’ The Shrovetide sculpture is destined to stay in the Burston family for generations but will, at intervals, be put on public display in Ashbourne. Plans are being made to have a public unveiling of the finished piece in the town to which members of the community, the Shrovetide committee and the players whose faces are forever recorded on the memory box will be welcomed.

Download the PDF to see the full article as it appeared in Derbyshire Life Magazine March 2020